Impact of Personal Care Formulations on the Environment

Image used for illustrative purposes only

In the last article, Suman Majumder introduced the 12 principles of Green Chemistry. In the second instalment of the series, he articulates the relevance of Green Chemistry in Personal Care formulations.

The world we live in is ever-changing. The global population has already reached seven billion and is forecasted to reach nine billion by 2050. It is obvious that the planet’s resources cannot cope with such an exploding human population, especially at existing consumption rates. Human activities have contributed to, or been responsible for, climate change, loss of biodiversity, destruction of habitat for many species and other such environmental damage. Human behaviour and consumption patterns need to change if the planet is to adequately feed another two billion mouths. Sustainable living will be the key mantra for the next decade. Consumer behaviour is also changing. As consumers become more informed, they will demand more from the products they buy. Higher education levels, the Internet and growing use of the same are making consumers more informed than at any other time in history. They are questioning product origins, production methods and ecosystem implications, as well as safety issues. This rise in ethical consumerism is having a significant impact on the cosmetics industry. Cosmetic and ingredient companies are increasingly audited by retailers and NGOs looking to safeguard consumer interests through regular scrutiny.

It is against this backdrop that the idea of revisiting “Green Chemistry” and its impact on personal care formulation becomes relevant. With a growing deficit of resources and rising ethical consumerism, how can the cosmetics industry become more sustainable? What are the best practices in sustainable product development? What areas are cosmetic scientists focusing on, and what areas need to be improved?

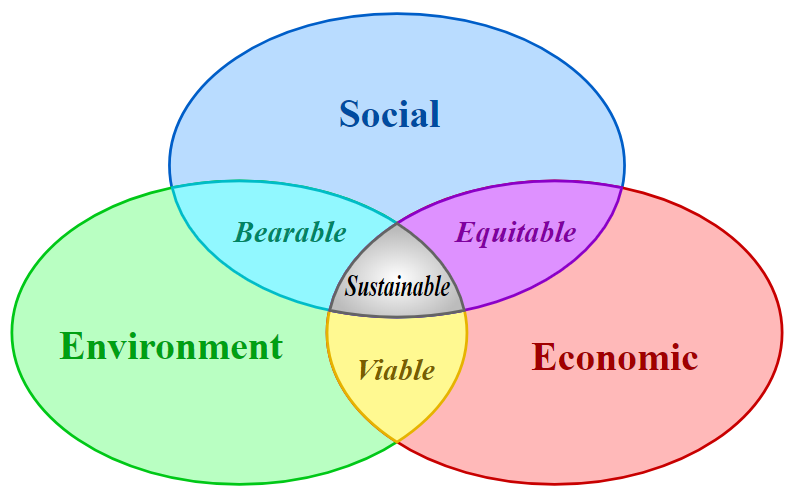

The three pillars of Sustainability- Social, Environmental and Economic should also be considered when applying these principles of “Green Chemistry” to the personal care product

Image for illustration purpose only.

Environmental dimension requires that natural environmental capital remains intact which means that the source and sink functions of the environment should not be degraded. The extraction of renewable resources should not exceed the rate at which they are renewed, and the absorptive capacity of the environment to assimilate wastes should not be exceeded.

Social dimension requires that the cohesion of society and its ability to work towards common goals be maintained. Individual goals, such as those for health and well-being, nutrition, shelter, education, and cultural needs should be met.

Economic dimension is considered when development, which moves towards social and environmental sustainability, is commercially feasible.

Cosmetics and personal care products are made from several chemical constituents which make the body of the formulation, enhance the stability of the same, improve the aesthetics and sensorial aspect of the formulation.

Raw materials generally used in cosmetics:

- a) Oils – Hydrocarbons, Vegetable oils & fats, Waxes, Esters, Higher alcohols, Fatty acids & Silicone

- b) Surfactants – Anionic, Cationic, Tertiary amines, Amphoteric, Non-ionic c) Polymers – Thickening, Improving texture, Hair setting, Stabilizing emulsion

- d) Glycol – Moisturizer, Stabilizer, Solvent, Solubilizers of aroma chemicals, Disperser of polymers

- e) Others – Active molecules, Colouring agents, Preservatives, Antioxidants, Chelating agent.

Thus, cosmetics are closely linked to the chemical industry. Indeed, many of the larger chemical companies in the world supply speciality chemicals to the cosmetics industry; such companies include BASF, Dow Chemical, Evonik, Rhodia and Eastman Chemical. The big chemical conglomerates have a heavy focus on environmental safety, sustainable sourcing programs with time-bound targets. But small companies who do not have governance sometimes follow unethical business practices for the short-term profit, which result in environmental pollution and eventually become associated with the cosmetics industry.

Cosmetic companies are also coming under the radar for natural ingredient sourcing. The industry is one of the largest users of palm oil, a vegetable oil that is predominantly grown in Indonesia and Malaysia. Unethical sourcing of palm oil has been the cause for the destruction of tropical rainforests, threatening the habitat of endangered orang-utans. Unilever, one of the largest cosmetic companies in the world, was named as a buyer of unethical palm oil by Greenpeace in November 2009. The move led Unilever to drop its Indonesian supplier and make a commitment to only source sustainable palm oil certified by the Roundtable of Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO). Green initiatives from big chemical companies like Henkel Corp. who manufactures alkyl polyglycoside surfactants, a class of non-ionic surfactants manufactured from renewable resources including fatty alcohol, derived from coconut and palm oils, and glucose derived from corn starch. But, unfortunately, while these materials are renewable, they can be far from environmentally benign, as biodiverse forests around the globe have been cleared and replaced by monocultures of oil palms. A scheme to certify palm oil as sustainable has been in operation since late 2008, but of the 40 million tonnes of palm oil produced annually, only around 1.7 million tonnes is so far covered.

The environmental damage caused by cosmetic finished products is also coming under the spotlight. Several studies have reported on the adverse effects of cosmetic ingredients on the environment. In August 2012, U.S federal authorities found Minnesota waterways to be contaminated by cosmetic ingredients. Anti-microbial ingredients like triclocarban and triclosan are present in soaps, disinfectants, and sanitisers; they are getting into fresh waterways from waste treatment plants after entering sewers from consumer households. Not only do these chemicals have endocrine-disrupting abilities, but also are toxic to aquatic bacteria. Triclosan also inhibits photosynthesis in diatom algae, responsible for a large part of the photosynthesis on Earth.

Microplastics in formulations are also accumulating in the seas and oceans, disrupting marine ecosystems. Microbeads are used in soaps, scrubs, and shower gels for exfoliating and texturizing purposes. Since they are slowly biodegradable, they accumulate in water and are ingested by marine life and create damage. So, now these are banned from use in cosmetic products since 2014.

The safety of cosmetic ingredients is also the subject of much concern and is an active subject of research. Studies suggested that phthalates – widely used as solvents in hair sprays, nail varnishes and perfumes – act as potential endocrine disruptors. Parabens, as chemical preservatives present in thousands of cosmetic products, are known to mimic oestrogen and are linked to breast cancer. Other cosmetic chemicals that are linked to health hazards include aluminium salts, petrochemicals oils, triclosan, formaldehyde, mercury, and other heavy metals. Although many of these cosmetic chemicals may be associated with health risks, however, scientific evidence is often lacking. Consumer perception is often stronger than reality when it comes to product safety. Some of the naturally tagged chemicals like natural polyphenols in spices, fruits may be considered often as safe and can be used in abundance may pose serious health issues for many consumers who are allergic to those naturally occurring chemicals. Research in personalized safety tests for natural cosmetics is still at its infancy. But, with the growing demand for greener and personalized cosmetics and personal care products in the cosmetics industry, this field may be in high demand.

A major concern about the safety of such chemicals is the variation in regulations between different regions and countries. For example, the EU banned the use of phthalates in 2003, however, it is still permitted in many other regions. Some countries lack enforcement of regulations, leading to potentially serious incidents. December 2012, the EcoWaste Coalition found that mercury-laden cosmetics were being sold in the Philippines. The national government had banned the sale of cosmetics with mercury because of health risks, but many retailers were ignoring the ban because of laxity in enforcement.

Image used for illustrative purposes only

Metrics for measurement

Cosmetics industry will be under constant scrutiny because of the perceived nature of cosmetic products. Apart from the ethical issues surrounding animal testing, they are often criticised for their selection and use of raw materials, environmental impacts, and safety issues of finished products. Cosmetic companies moving towards greener chemicals and have sustainability as their corporate agenda often makes these initiatives big through the marketing campaign around these products in the market and through CSR and Corporate Sustainability reporting. Over 80% of Global Fortune250 companies (G250) now disclose their sustainability performance in sustainability or corporate social responsibility reports. All cosmetic companies in the G500, including Procter & Gamble, Unilever, Johnson & Johnson, Henkel, and L’Oréal, are publishing CSR reports since 2012.

Direct communication of sustainable development to consumers is also considered by many cosmetic companies to promote their sustainability agenda and to build awareness with consumers. An example of point-of-sale communications is by the American natural cosmetics company, Kiss My Face. It is demonstrating its eco-consciousness with Greenhouse, an in-store point of purchase display that is not only recyclable but made from recycled materials. To make consumers aware of its efforts, Kiss MyFace provides the following explanation on the display: ‘Because you care, this display is planet-friendly’. To minimize waste and maximize recycled and sustainable resources, all corrugated components are from minimum of 90% recycled materials. Graphics are printed with non-polluting water solvent inks. Steel parts are made from 70% recycled material and powder coating on metal parts use non-VOC materials that eliminate airborne pollutants. Wood components are biodegradable and treated with an environmentally safe lacquer.’

Aveda created a popular public outreach programme to recycle polypropylenebottle caps. Aveda’s ‘Recycle Caps with Aveda’ campaign has become a popular and effective marketing technique to show the company’s concern for the environment, whilst partnering with schools and environmentally conscious consumers.

So are the big chemical industries looking for sustainable natural resources for making greener chemicals? The challenge is often the greener raw materials become more expensive due to low supplies and hence become economically not feasible to be incorporated in cosmetic or personal care products since the synthetic analogues are much cheaper and easily accessible.

When it comes to the application of “Green Chemistry” in a cosmetic or personal care product launched by Cosmetic companies, the corporate carbon footprint can be defined as “the total set of greenhouse gas(GHG) emissions caused by an organization.”GHGs can be emitted through transport, the production and consumption of fuels, manufacturing goods, materials, wood as well as the construction of roads and buildings, and the provision of services. For simplicity of reporting and interpretation, the emission of all GHGs is typically expressed in terms of the effective equivalent amount of carbon dioxide.

- Raw Material & Packaging

- Production

- Distribution, Use & End of life

The other important metrics followed is Inventory analysis followed by an impact assessment. This phase of life cycle analysis (LCA) is aimed at evaluating the significance of potential environmental impacts based on the life cycle impact (LCI)flow results. Classical life-cycle impact assessment (LCIA) consists of the following mandatory elements: a) selection of impact categories, category indicators, and characterization models; b) the classification stage, where the inventory parameters are sorted and assigned to specific impact categories; c) impact measurement, where the categorized LCI flows are characterized, using one of many possible LCIA methodologies, into common equivalence units that are then summed to provide an overall impact category total.

Author : Suman Majumder . PhD, FRSC

suman.majumder1970@gmail .com

Dr Suman Majumder is a senior research and management professional with 20 years of postdoctoral experience in Organic Synthesis and Product Development for various industry sectors including Pharmaceutical, FMCG (Food, Personal Care, Laundry, Hygiene), Packaging and Agro-chemical. He was associated with Industrial R&D with companies like TCG Lifesciences, Dow Chemicals, Sigma-Aldrich, Unilever, Loreal, Avery Dennison and is presently the Head – R&D at Bajaj Consumer Care.

Nice response in return of this difficulty with solid arguments and

telling everything about that.

ST666 – Nhà Cái Uy Tín Với Nhiều Khuyến Mãi Hấp Dẫn

ST666 là một trong những sòng bài trực tuyến uy tín nhất, mang đến cho các thành viên nhiều chương trình khuyến mãi đa dạng và hấp dẫn. Chúng tôi luôn hy vọng rằng những ưu đãi đặc biệt này sẽ mang lại trải nghiệm cá cược tuyệt vời cho tất cả thành viên của mình.

Khuyến Mãi Nạp Đầu Thưởng 100%

NO.1: Thưởng 100% lần nạp đầu tiên Thông thường, các khuyến mãi nạp tiền lần đầu đi kèm với yêu cầu vòng cược rất cao, thường từ 20 vòng trở lên. Tuy nhiên, ST666 hiểu rằng người chơi thường đắn đo khi quyết định nạp tiền vào sòng bài trực tuyến. Do đó, chúng tôi chỉ yêu cầu 8 vòng cược, cho phép người chơi rút tiền một cách nhanh chóng trong vòng 5 phút.

Thưởng 100% khi Đăng Nhập ST666

NO.2: Thưởng 16% mỗi ngày ST666 mang đến cho bạn một ưu đãi không thể bỏ lỡ. Mỗi khi bạn nạp tiền vào tài khoản hàng ngày, bạn sẽ được nhận thêm 16% số tiền nạp. Đây là cơ hội tuyệt vời dành cho những ai yêu thích cá cược trực tuyến và muốn gia tăng cơ hội chiến thắng của mình.

Bảo Hiểm Hoàn 10% Mỗi Ngày

NO.3: Bảo hiểm hoàn tiền 10% ST666 không chỉ hỗ trợ người chơi trong những lần may mắn mà còn luôn đồng hành khi bạn không gặp may. Chương trình khuyến mãi “bảo hiểm hoàn tiền 10% tổng tiền nạp mỗi ngày” là cách chúng tôi khích lệ và động viên tinh thần game thủ, giúp bạn tiếp tục hành trình chinh phục các thử thách cá cược.

Giới Thiệu Bạn Bè Thưởng 999K

NO.4: Giới thiệu bạn bè – Thưởng 999K Chương trình “Giới thiệu bạn bè” của ST666 giúp bạn có cơ hội cá cược cùng bạn bè và người thân. Không những vậy, bạn còn có thể nhận được phần thưởng lên đến 999K khi giới thiệu người bạn của mình tham gia ST666. Đây chính là một ưu đãi tuyệt vời giúp bạn vừa có thêm người đồng hành, vừa nhận được thưởng hấp dẫn.

Đăng Nhập Nhận Ngay 280K

NO.5: Điểm danh nhận thưởng 280K Nếu bạn là thành viên thường xuyên của ST666, hãy đừng quên nhấp vào hộp quà hàng ngày để điểm danh. Chỉ cần đăng nhập liên tục trong 7 ngày, cơ hội nhận thưởng 280K sẽ thuộc về bạn!

Kết Luận

ST666 luôn nỗ lực không ngừng để mang lại những chương trình khuyến mãi hấp dẫn và thiết thực nhất cho người chơi. Dù bạn là người mới hay đã gắn bó lâu năm với nền tảng, ST666 cam kết cung cấp trải nghiệm cá cược tốt nhất, an toàn và công bằng. Hãy tham gia ngay để không bỏ lỡ các cơ hội tuyệt vời từ ST666!

Профессиональный сервисный центр по ремонту компьютерных видеокарт по Москве.

Мы предлагаем: ремонт видеокарт nvidia москва

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

Алкогольный запой представляет собой критическое состояние, требующее немедленного медицинского вмешательства. Стационарное лечение является оптимальным решением для безопасного и эффективного вывода из запоя, особенно в тяжелых случаях интоксикации. В этой статье мы подробно рассмотрим процесс стационарного лечения, его анонимность, скорость и роль нарколога в восстановлении пациентов.

Получить дополнительную информацию – вывод из запоя в стационаре шахты

Анонимное лечение запоя может осуществляться в разных условиях, учитывая степень тяжести состояния и предпочтения пациента. Рассмотрим два основных варианта: стационарное и амбулаторное лечение.

Подробнее можно узнать тут – вывод из запоя анонимно клиник нн

Цены на вывод из запоя на дому могут колебаться от 7000 до 25000 рублей. Эта сумма может изменяться в зависимости от необходимых процедур, состояния пациента и используемых медикаментов. Например, применение специфических препаратов для детоксикации увеличивает общую стоимость.

Углубиться в тему – вывод из запоя цены новый уренгой

Алкогольная зависимость является серьезной проблемой, требующей комплексного подхода для успешного лечения. Запой, как состояние, характеризуется длительным непрерывным потреблением алкогольных напитков, что приводит к физической и психической зависимости. Данное состояние нарушает функционирование внутренних органов, увеличивает вероятность развития опасных заболеваний, таких как алкогольный делирий. Эффективный вывод из запоя — это важнейший этап в процессе лечения зависимости, который может проводиться как в условиях стационара, так и на дому, в зависимости от состояния пациента.

Узнать больше – вывод из запоя на дому саратов круглосуточно

Именно абстиненция зачастую становится непреодолимым препятствием на пути к выздоровлению, заставляя человека вновь и вновь возвращаться к употреблению. Кроме того, зависимость негативно сказывается на когнитивных функциях, приводит к деградации личности, разрушает социальные связи, делая практически невозможным нормальное функционирование человека в обществе.

Подробнее тут – вывод из запоя капельница сочи

Проблема алкогольной зависимости остается актуальной в современном обществе, затрагивая жизни многих людей. Запой — это состояние, при котором человек не может контролировать потребление алкоголя, что приводит к тяжелым последствиям для здоровья и социальной дезадаптации. Вывод из запоя — это сложный процесс, требующий своевременного вмешательства специалистов, и одним из вариантов является оказание помощи на дому.

Изучить вопрос глубже – вывод из запоя на дому нефтекамск

русское порно

Информационный сайт с интересной темы.

http://www.ambmedan.ac.id/beasiswa-taruna-amb-medan

Интересная информационнная статья общей тематики.

https://newslocal.uk/who-do-you-think-you-are-fans-blown-away-by-vicky-mcclures-story-in-saddest-episode

Интересные и увлекательные статьи у нас.

https://rafengineering.eu/bg/component/k2/item/5-jerky-shank-chicken-boudin?start=56470

Интересная информационнная статья медицинской тематики.

https://herbach-haase.de/september-2010

Интересные статьи на данном сайте.

https://ventaelcruce.es/vulkan-sin-city-casino-erfahrungen-200-einzahlungsbonus-55-freispiele-fur-devils-delight-2

Статьи на различные темы на страницах сайта.

https://www.mirshartenziel.nl/tips-on-how-to-build-an-essay

I like the valuable info you provide in your articles. I’ll bookmark your blog and check again here frequently.

I’m quite sure I will learn a lot of new stuff right here! Best

of luck for the next!

Современное общество сталкивается с множеством проблем, связанных с алкоголем. Зависимость от спиртных напитков негативно сказывается на здоровье, психическом состоянии и жизни людей. Вывод из запоя является важным этапом в процессе восстановления, который требует комплексного подхода и профессионального вмешательства. Эта процедура не только облегчает физические страдания, но также играет ключевую роль в психоэмоциональном восстановлении пациентов.

Подробнее можно узнать тут – вывод из запоя цены в пушкино

Алкогольная зависимость требует комплексного подхода. Профессионалы знают, как помочь пациенту выйти из запойного состояния с минимальными последствиями. На этом пути важны не только медицинские, но и психологические аспекты, которые способствуют восстановлению.

Получить больше информации – вывод из запоя в стационаре недорого

Алкогольная зависимость является одной из наиболее распространённых форм аддиктивного поведения, имеющей значительное влияние на здоровье человека. Запой, как состояние длительного употребления спиртных напитков, приводит к серьезным физическим и психическим расстройствам. Вывод из запоя представляет собой процесс, требующий комплексного подхода с применением медицинских методов. Анонимное лечение даёт возможность людям избавиться от зависимости, не опасаясь общественного мнения.

Получить дополнительные сведения – вывод из запоя анонимно зарайск

Круглосуточный вывод из запоя представляет собой неотложную медицинскую процедуру, направленную на оказание помощи пациентам с алкогольной интоксикацией. Запой — это состояние, при котором человек теряет контроль над потреблением алкоголя, что приводит к серьезным последствиям для здоровья. Это состояние требует профессионального подхода, так как алкогольная интоксикация может вызвать опасные осложнения и даже угрожать жизни.

Выяснить больше – вывод из запоя люберцы круглосуточно

Процесс включает мероприятия, направленные на устранение симптомов алкогольной интоксикации, восстановление нормального функционирования органов и систем, а также психоэмоциональной стабильности. Ключевым этапом является инфузионная терапия, которая помогает нормализовать водно-электролитный баланс и снять абстинентный синдром.

Подробнее можно узнать тут – вывод из запоя на дому недорого зеленоград

Миссия клиники “Ариадна” заключается в оказании качественной и всесторонней помощи людям, страдающим от различных форм зависимости. Мы понимаем, что успешное лечение невозможно без индивидуального подхода, поэтому каждый пациент получает возможность пройти диагностику, после которой разрабатывается персонализированный план терапии.

Исследовать вопрос подробнее – вывод из запоя в стационаре лобня

Loved this article! This topic really resonates with me. I appreciate the insights you provided.

This is a unique take on the subject. Thanks for shedding light on this issue; This has given me

a lot to think about!

This is a must-read for everyone and I’m curious

to hear what others think about it! Overall, I think this topic is crucial for our community, and discussions like

this help us grow and learn together. Thanks again for

this valuable content!

Here is my web-site … Chicago Press (bysee3.com)

บาคาร่า

เล่นบาคาร่าแบบรวดเร็วทันใจกับสปีดบาคาร่า

ถ้าคุณเป็นแฟนตัวยงของเกมไพ่บาคาร่า คุณอาจจะเคยชินกับการรอคอยในแต่ละรอบการเดิมพัน และรอจนดีลเลอร์แจกไพ่ในแต่ละตา แต่คุณรู้หรือไม่ว่า ตอนนี้คุณไม่ต้องรออีกต่อไปแล้ว เพราะ SA Gaming ได้พัฒนาเกมบาคาร่าโหมดใหม่ขึ้นมา เพื่อให้ประสบการณ์การเล่นของคุณน่าตื่นเต้นยิ่งขึ้น!

ที่ SA Gaming คุณสามารถเลือกเล่นไพ่บาคาร่าในโหมดที่เรียกว่า สปีดบาคาร่า (Speed Baccarat) โหมดนี้มีคุณสมบัติพิเศษและข้อดีที่น่าสนใจมากมาย:

ระยะเวลาการเดิมพันสั้นลง — คุณไม่จำเป็นต้องรอนานอีกต่อไป ในโหมดสปีดบาคาร่า คุณจะมีเวลาเพียง 12 วินาทีในการวางเดิมพัน ทำให้เกมแต่ละรอบจบได้รวดเร็ว โดยเกมในแต่ละรอบจะใช้เวลาเพียง 20 วินาทีเท่านั้น

ผลตอบแทนต่อผู้เล่นสูง (RTP) — เกมสปีดบาคาร่าให้ผลตอบแทนต่อผู้เล่นสูงถึง 4% ซึ่งเป็นมาตรฐานความเป็นธรรมที่ผู้เล่นสามารถไว้วางใจได้

การเล่นเกมที่รวดเร็วและน่าตื่นเต้น — ระยะเวลาที่สั้นลงทำให้เกมแต่ละรอบดำเนินไปอย่างรวดเร็ว ทันใจ เพิ่มความสนุกและความตื่นเต้นในการเล่น ทำให้ประสบการณ์การเล่นของคุณยิ่งสนุกมากขึ้น

กลไกและรูปแบบการเล่นยังคงเหมือนเดิม — แม้ว่าระยะเวลาจะสั้นลง แต่กลไกและกฎของการเล่น ยังคงเหมือนกับบาคาร่าสดปกติทุกประการ เพียงแค่ปรับเวลาให้เล่นได้รวดเร็วและสะดวกขึ้นเท่านั้น

นอกจากสปีดบาคาร่าแล้ว ที่ SA Gaming ยังมีโหมด No Commission Baccarat หรือบาคาร่าแบบไม่เสียค่าคอมมิชชั่น ซึ่งจะช่วยให้คุณสามารถเพลิดเพลินไปกับการเล่นได้โดยไม่ต้องกังวลเรื่องค่าคอมมิชชั่นเพิ่มเติม

เล่นบาคาร่ากับ SA Gaming คุณจะได้รับประสบการณ์การเล่นที่สนุก ทันสมัย และตรงใจมากที่สุด!

This is a topic which is near to my heart…

Take care! Exactly where are your contact details though?

Pagar bayi yang multifungsi benar-benar pilihan tepat untuk

melindungi keamanan si kecil. Ide yang sangat bermanfaat!

rgbet

Bạn đang tìm kiếm những trò chơi hot nhất và thú vị nhất tại sòng bạc trực tuyến? RGBET tự hào giới thiệu đến bạn nhiều trò chơi cá cược đặc sắc, bao gồm Baccarat trực tiếp, máy xèng, cá cược thể thao, xổ số và bắn cá, mang đến cho bạn cảm giác hồi hộp đỉnh cao của sòng bạc! Dù bạn yêu thích các trò chơi bài kinh điển hay những máy xèng đầy kịch tính, RGBET đều có thể đáp ứng mọi nhu cầu giải trí của bạn.

RGBET Trò Chơi của Chúng Tôi

Bạn đang tìm kiếm những trò chơi hot nhất và thú vị nhất tại sòng bạc trực tuyến? RGBET tự hào giới thiệu đến bạn nhiều trò chơi cá cược đặc sắc, bao gồm Baccarat trực tiếp, máy xèng, cá cược thể thao, xổ số và bắn cá, mang đến cảm giác hồi hộp đỉnh cao của sòng bạc! Dù bạn yêu thích các trò chơi bài kinh điển hay những máy xèng đầy kịch tính, RGBET đều có thể đáp ứng mọi nhu cầu giải trí của bạn.

RGBET Trò Chơi Đa Dạng

Thể thao: Cá cược thể thao đa dạng với nhiều môn từ bóng đá, tennis đến thể thao điện tử.

Live Casino: Trải nghiệm Baccarat, Roulette, và các trò chơi sòng bài trực tiếp với người chia bài thật.

Nổ hũ: Tham gia các trò chơi nổ hũ với tỷ lệ trúng cao và cơ hội thắng lớn.

Lô đề: Đặt cược lô đề với tỉ lệ cược hấp dẫn.

Bắn cá: Bắn cá RGBET mang đến cảm giác chân thực và hấp dẫn với đồ họa tuyệt đẹp.

RGBET – Máy Xèng Hấp Dẫn Nhất

Khám phá các máy xèng độc đáo tại RGBET với nhiều chủ đề khác nhau và tỷ lệ trả thưởng cao. Những trò chơi nổi bật bao gồm:

RGBET Super Ace

RGBET Đế Quốc Hoàng Kim

RGBET Pharaoh Treasure

RGBET Quyền Vương

RGBET Chuyên Gia Săn Rồng

RGBET Jackpot Fishing

Vì sao nên chọn RGBET?

RGBET không chỉ cung cấp hàng loạt trò chơi đa dạng mà còn mang đến một hệ thống cá cược an toàn và chuyên nghiệp, đảm bảo mọi quyền lợi của người chơi:

Tốc độ nạp tiền nhanh chóng: Chuyển khoản tại RGBET chỉ mất vài phút và tiền sẽ vào tài khoản ngay lập tức, giúp bạn không bỏ lỡ bất kỳ cơ hội nào.

Game đổi thưởng phong phú: Từ cá cược thể thao đến slot game, RGBET cung cấp đầy đủ trò chơi giúp bạn tận hưởng mọi phút giây thư giãn.

Bảo mật tuyệt đối: Với công nghệ mã hóa tiên tiến, tài khoản và tiền vốn của bạn sẽ luôn được bảo vệ một cách an toàn.

Hỗ trợ đa nền tảng: Bạn có thể chơi trên mọi thiết bị, từ máy tính, điện thoại di động (iOS/Android), đến nền tảng H5.

Tải Ứng Dụng RGBET và Nhận Khuyến Mãi Lớn

Hãy tham gia RGBET ngay hôm nay để tận hưởng thế giới giải trí không giới hạn với các trò chơi thể thao, thể thao điện tử, casino trực tuyến, xổ số, và slot game. Quét mã QR và tải ứng dụng RGBET trên điện thoại để trải nghiệm game tốt hơn và nhận nhiều khuyến mãi hấp dẫn!

Tham gia RGBET để bắt đầu cuộc hành trình cá cược đầy thú vị ngay hôm nay!

When I originally left a comment I appear to have clicked on the -Notify me when new comments

are added- checkbox and from now on every time a comment is added I get 4 emails with the same comment.

Perhaps there is a means you can remove me from

that service? Kudos!

Профессиональный сервисный центр по ремонту компьютерных видеокарт по Москве.

Мы предлагаем: стоимость ремонта видеокарты

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

Сервисный центр предлагает ремонт электросамоката tanko адреса ремонт электросамокатов tanko в москве

Свежие и смешные шутки http://shutki-anekdoty.ru/korotkie-anekdoty.

Alana melihat-lihat Pinterest, sorot matanya terpaku

pada gawai saat inspirasi pakaian memenuhi feed-nya. Mode selalu menarik hatinya, namun menemukan ansambel yang tepat

untuk pesta malam ini terasa mustahil. Tak ada yang tampak istimewa.

Setiap unggahan tampak terlalu sederhana atau berlebihan.

Kemudian, sebuah nada notifikasi menghentikan rasa kecewanya.

Sebuah notifikasi muncul – “Pakaian yang Direkomendasikan: Terinspirasi dari pin terbaru Anda.” Karena

penasaran, dia lalu membukanya. Pakaiannya sempurna:

gaun dengan corak bunga bergaya vintage, di-mix and match dengan sepatu bot pergelangan kaki, layered accessories, dan cropped leather jacket untuk membuat perpaduan antara nuansa feminin dengan tampilan edgy.

Ini persis seperti apa yang ada di imajinasinya

di dalam benaknya, namun tak mampu dia ungkapkan.

Caption dari gambar itu tertulis: “Anda tak

akan menyangka ke mana tampilan ini akan membawamu.” Alana tersenyum dan menyimpannya di board

miliknya, karena ia tahu bahwa itu yang pas untuk malam

itu. Dia dengan cepat mengambil apa yang ada di lemarinya, jantungnya berdebar cepat karena bersemangat.

Saat sampai di acara, energinya sangat bersemangat. Ia merasakan dirinya percaya diri, bahkan bercahaya, seolah-olah pakaian itu telah membuka sesuatu di dalam hatinya.

Saat berjalan menuju minuman, dia melihat seorang pria yang berdiri di samping bar, matanya tertuju padanya.

Pakaiannya juga tak kalah bergaya, kombinasi kasual

dan trendi yang terkoordinasi dengan baik membuatnya terlihat mencolok di tengah

keramaian.

Thank you for the auspicious writeup. It in reality was once a

entertainment account it. Look advanced to more introduced agreeable

from you! By the way, how could we be in contact?

เล่นบาคาร่าแบบรวดเร็วทันใจกับสปีดบาคาร่า

ถ้าคุณเป็นแฟนตัวยงของเกมไพ่บาคาร่า คุณอาจจะเคยชินกับการรอคอยในแต่ละรอบการเดิมพัน และรอจนดีลเลอร์แจกไพ่ในแต่ละตา แต่คุณรู้หรือไม่ว่า ตอนนี้คุณไม่ต้องรออีกต่อไปแล้ว เพราะ SA Gaming ได้พัฒนาเกมบาคาร่าโหมดใหม่ขึ้นมา เพื่อให้ประสบการณ์การเล่นของคุณน่าตื่นเต้นยิ่งขึ้น!

ที่ SA Gaming คุณสามารถเลือกเล่นไพ่บาคาร่าในโหมดที่เรียกว่า สปีดบาคาร่า (Speed Baccarat) โหมดนี้มีคุณสมบัติพิเศษและข้อดีที่น่าสนใจมากมาย:

ระยะเวลาการเดิมพันสั้นลง — คุณไม่จำเป็นต้องรอนานอีกต่อไป ในโหมดสปีดบาคาร่า คุณจะมีเวลาเพียง 12 วินาทีในการวางเดิมพัน ทำให้เกมแต่ละรอบจบได้รวดเร็ว โดยเกมในแต่ละรอบจะใช้เวลาเพียง 20 วินาทีเท่านั้น

ผลตอบแทนต่อผู้เล่นสูง (RTP) — เกมสปีดบาคาร่าให้ผลตอบแทนต่อผู้เล่นสูงถึง 4% ซึ่งเป็นมาตรฐานความเป็นธรรมที่ผู้เล่นสามารถไว้วางใจได้

การเล่นเกมที่รวดเร็วและน่าตื่นเต้น — ระยะเวลาที่สั้นลงทำให้เกมแต่ละรอบดำเนินไปอย่างรวดเร็ว ทันใจ เพิ่มความสนุกและความตื่นเต้นในการเล่น ทำให้ประสบการณ์การเล่นของคุณยิ่งสนุกมากขึ้น

กลไกและรูปแบบการเล่นยังคงเหมือนเดิม — แม้ว่าระยะเวลาจะสั้นลง แต่กลไกและกฎของการเล่น ยังคงเหมือนกับบาคาร่าสดปกติทุกประการ เพียงแค่ปรับเวลาให้เล่นได้รวดเร็วและสะดวกขึ้นเท่านั้น

นอกจากสปีดบาคาร่าแล้ว ที่ SA Gaming ยังมีโหมด No Commission Baccarat หรือบาคาร่าแบบไม่เสียค่าคอมมิชชั่น ซึ่งจะช่วยให้คุณสามารถเพลิดเพลินไปกับการเล่นได้โดยไม่ต้องกังวลเรื่องค่าคอมมิชชั่นเพิ่มเติม

เล่นบาคาร่ากับ SA Gaming คุณจะได้รับประสบการณ์การเล่นที่สนุก ทันสมัย และตรงใจมากที่สุด!

Excellent beat ! I would like to apprentice whilst you amend your site,

how could i subscribe for a blog web site? The account aided me a applicable deal.

I were a little bit acquainted of this your broadcast offered shiny

transparent concept jilislot

Stablecoin TRON-based Transaction Verification and Anti-Money Laundering (Anti-Money Laundering) Procedures

As cryptocurrencies like USDT TRC20 gain popularity for rapid and affordable transfers, the demand for security and compliance with Anti-Money Laundering standards increases. Here’s how to check USDT TRON-based transactions and confirm they’re not linked to unlawful operations.

What does it mean USDT TRC20?

USDT TRC20 is a cryptocurrency on the TRX ledger, priced in correspondence with the USD. Famous for its cheap transfers and quickness, it is widely used for cross-border transactions. Verifying payments is crucial to prevent connections to money laundering or other illegal acts.

Verifying USDT TRC20 Transactions

TRONSCAN — This blockchain viewer allows individuals to track and validate Tether TRC20 transactions using a account ID or transaction ID.

Supervising — Experienced users can observe anomalous patterns such as high-volume or fast transactions to detect unusual actions.

AML and Criminal Crypto

Financial Crime Prevention (AML) rules help block illegal money transfers in cryptocurrency. Tools like Chain Analysis and Elliptic permit businesses and crypto markets to detect and prevent criminal crypto, which refers to funds related to unlawful operations.

Tools for Compliance

TRX Explorer — To validate USDT TRC20 payment details.

Chain Analysis and Elliptic — Employed by crypto markets to confirm AML adherence and follow illicit activities.

Final Thoughts

Guaranteeing protected and legal USDT TRC20 transactions is critical. Services like TRX Explorer and Anti-Money Laundering tools support protect participants from engaging with dirty cryptocurrency, supporting a protected and lawful digital market.

Наша компания помогает не только частным клиентам, но и малому и среднему бизнесу, предоставляя доступ к микрозаймам на выгодных условиях. Мы понимаем, насколько важно быстро получить финансовую поддержку для развития бизнеса, и предлагаем лучшие решения, которые помогут вашему делу расти и процветать.

займ займы Казахстан .

I have read so many content on the topic of the blogger lovers but this post is in fact a good article, keep it up.

Sweet blog! I found it while searching on Yahoo News.

Do you have any suggestions on how to get listed in Yahoo News?

I’ve been trying for a while but I never seem to get

there! Thank you

Интересная информационнная статья общей тематики.

http://ernstrosen.com/uncategorized/what-ive-learned-from-road-trips

Интересные и увлекательные статьи у нас.

https://www.sisteautovalle.com/logo-s-2

Информационный сайт с интересной темы.

http://www.centralparknursery.co.uk/product/premium-quality-2

Интересные статьи на данном сайте.

https://www.barnalliance.org/2012/08/13/4-h-barn-owl-day-in-schenectady-county-ny/owl-kids-in-barn

Интересная информационнная статья медицинской тематики.

https://kyst-shirt.com/product/hoodie-olberg-west

Статьи на различные темы на страницах сайта.

https://kahverengicafeeregli.com/2020/08/22/efsaneler-kenti-karadeniz-eregli

Прикольные видео http://shutki-anekdoty.ru/videos.

สล็อต888

สล็อต888 เป็นหนึ่งในแพลตฟอร์มเกมสล็อตออนไลน์ที่ได้รับความนิยมสูงสุดในปัจจุบัน โดยมีความโดดเด่นด้วยการให้บริการเกมสล็อตที่หลากหลายและมีคุณภาพ รวมถึงฟีเจอร์ที่ช่วยให้ผู้เล่นสามารถเพลิดเพลินกับการเล่นได้อย่างเต็มที่ ในบทความนี้ เราจะมาพูดถึงฟีเจอร์และจุดเด่นของสล็อต888 ที่ทำให้เว็บไซต์นี้ได้รับความนิยมเป็นอย่างมาก

ฟีเจอร์เด่นของ PG สล็อต888

ระบบฝากถอนเงินอัตโนมัติที่รวดเร็ว สล็อต888 ให้บริการระบบฝากถอนเงินแบบอัตโนมัติที่สามารถทำรายการได้ทันที ไม่ต้องรอนาน ไม่ว่าจะเป็นการฝากหรือถอนก็สามารถทำได้ภายในไม่กี่วินาที รองรับการใช้งานผ่านทรูวอลเล็ทและช่องทางอื่น ๆ โดยไม่มีขั้นต่ำในการฝากถอน

รองรับทุกอุปกรณ์ ทุกแพลตฟอร์ม ไม่ว่าคุณจะเล่นจากอุปกรณ์ใดก็ตาม สล็อต888 รองรับทั้งคอมพิวเตอร์ แท็บเล็ต และสมาร์ทโฟน ไม่ว่าจะเป็นระบบ iOS หรือ Android คุณสามารถเข้าถึงเกมสล็อตได้ทุกที่ทุกเวลาเพียงแค่มีอินเทอร์เน็ต

โปรโมชั่นและโบนัสมากมาย สำหรับผู้เล่นใหม่และลูกค้าประจำ สล็อต888 มีโปรโมชั่นต้อนรับ รวมถึงโบนัสพิเศษ เช่น ฟรีสปินและโบนัสเครดิตเพิ่ม ทำให้การเล่นเกมสล็อตกับเราเป็นเรื่องสนุกและมีโอกาสทำกำไรมากยิ่งขึ้น

ความปลอดภัยสูงสุด เรื่องความปลอดภัยเป็นสิ่งที่สล็อต888 ให้ความสำคัญเป็นอย่างยิ่ง เราใช้เทคโนโลยีการเข้ารหัสข้อมูลขั้นสูงเพื่อปกป้องข้อมูลส่วนบุคคลของลูกค้า ระบบฝากถอนเงินยังมีมาตรการรักษาความปลอดภัยที่เข้มงวด ทำให้ลูกค้ามั่นใจในการใช้บริการกับเรา

ทดลองเล่นสล็อตฟรี

สล็อต888 ยังมีบริการให้ผู้เล่นสามารถทดลองเล่นสล็อตได้ฟรี ซึ่งเป็นโอกาสที่ดีในการทดลองเล่นเกมต่าง ๆ ที่มีอยู่บนเว็บไซต์ เช่น Phoenix Rises, Dream Of Macau, Ways Of Qilin, Caishens Wins และเกมยอดนิยมอื่น ๆ ที่มีกราฟิกสวยงามและรูปแบบการเล่นที่น่าสนใจ

ไม่ว่าจะเป็นเกมแนวผจญภัย เช่น Rise Of Apollo, Dragon Hatch หรือเกมที่มีธีมแห่งความมั่งคั่งอย่าง Crypto Gold, Fortune Tiger, Lucky Piggy ทุกเกมได้รับการออกแบบมาเพื่อสร้างประสบการณ์การเล่นที่น่าจดจำและเต็มไปด้วยความสนุกสนาน

บทสรุป

สล็อต888 เป็นแพลตฟอร์มที่ครบเครื่องเรื่องเกมสล็อตออนไลน์ ด้วยฟีเจอร์ที่ทันสมัย โปรโมชั่นที่น่าสนใจ และระบบรักษาความปลอดภัยที่เข้มงวด ทำให้คุณมั่นใจได้ว่าการเล่นกับสล็อต888 จะเป็นประสบการณ์ที่ปลอดภัยและเต็มไปด้วยความสนุก

кто проводит соут https://sout095.ru

процедура проведения соут спецоценка рабочих мест

охрана труда соут рабочего места пройти соут

Dirty cryptocurrency

Stablecoin TRC20 Payment Verification and Anti-Money Laundering (Anti-Money Laundering) Methods

As digital assets like USDT TRON-based rise in popularity for fast and low-cost transfers, the requirement for security and adherence with financial crime prevention rules grows. Here’s how to check Tether TRON-based transactions and guarantee they’re not related to illegal activities.

What does it mean USDT TRC20?

USDT TRC20 is a stablecoin on the TRON network, valued in line with the American dollar. Famous for its cheap transfers and velocity, it is frequently employed for international transactions. Validating transactions is crucial to avoid connections to financial crime or other illegal activities.

Verifying USDT TRC20 Transactions

TRONSCAN — This blockchain viewer enables individuals to follow and validate Tether TRC20 transfers using a wallet address or transaction ID.

Monitoring — Experienced participants can monitor suspicious behaviors such as significant or quick transactions to detect unusual activity.

AML and Criminal Crypto

Anti-Money Laundering (Anti-Money Laundering) regulations help stop illicit financial activity in cryptocurrency. Tools like Chainalysis and Elliptic permit businesses and exchanges to identify and stop illicit funds, which signifies money connected to illegal activities.

Instruments for Regulation

TRONSCAN — To check TRON-based USDT transfer details.

Chain Analysis and Elliptic Solutions — Used by trading platforms to confirm Anti-Money Laundering adherence and monitor illegal actions.

Summary

Ensuring secure and legitimate TRON-based USDT payments is crucial. Services like TRX Explorer and Anti-Money Laundering systems help protect traders from involving with dirty cryptocurrency, supporting a safe and regulated digital market.

Конфиденциальность способствует формированию доверительных отношений между пациентом и медицинским персоналом. Это важный элемент, так как открытое взаимодействие позволяет более точно диагностировать проблемы, связанные с зависимостью. Психологическая поддержка в анонимной обстановке становится значимой частью процесса реабилитации.

Выяснить больше – вывод из запоя в стационаре мытищи

Цена выведения из запоя на дому может варьироваться от 4000 до 18 000 рублей. Данный метод подразумевает оказание медицинской помощи пациенту в привычной домашней обстановке. Выездная бригада врачей проводит осмотр и оценку состояния, измеряя жизненно важные показатели и анализируя анамнез.

Ознакомиться с деталями – вывод из запоя на дому омск цены

Алкоголизм, являющийся хроническим заболеванием, характеризуется патологической зависимостью от этанола. Периоды запоя могут проявляться неконтролируемым потреблением алкоголя, что приводит к разнообразным медицинским осложнениям. Основными проблемами являются физическая и психологическая зависимость, что делает необходимым вывод из запоя. Этот процесс требует комплексного подхода с учётом индивидуальных особенностей каждого пациента. Анонимность в реабилитации имеет особое значение, позволяя избежать стигматизации и повышая шансы на успешное восстановление.

Выяснить больше – вывод из запоя анонимно

Круглосуточная помощь подразумевает возможность получения медицинской поддержки в любое время суток. Этот подход особенно актуален, так как состояние пациента с запоем может резко ухудшиться, требуя срочного вмешательства. Вывод из запоя на дому – это удобный метод, позволяющий пациенту оставаться в привычной обстановке.

Получить дополнительную информацию – вывод из запоя круглосуточно вывод нарколог

Процесс начинается с первичной диагностики. Квалифицированный нарколог проводит осмотр, собирает анамнез и выявляет степень зависимости. Это позволяет определить, насколько серьезно состояние пациента, и какие меры необходимо предпринять для его стабилизации.

Подробнее – вывод из запоя на дому истра

Зависимости часто сопровождаются физическими и психологическими расстройствами, которые требуют комплексного подхода. Мы понимаем, что успешное лечение невозможно без индивидуального подхода, что делает нашу клинику идеальным местом для тех, кто ищет помощь.

Узнать больше – вывод из запоя цена лыткарино

st666

ST666 – Nhà Cái Uy Tín Với Nhiều Khuyến Mãi Hấp Dẫn

ST666 là một trong những sòng bài trực tuyến uy tín nhất, mang đến cho các thành viên nhiều chương trình khuyến mãi đa dạng và hấp dẫn. Chúng tôi luôn hy vọng rằng những ưu đãi đặc biệt này sẽ mang lại trải nghiệm cá cược tuyệt vời cho tất cả thành viên của mình.

Khuyến Mãi Nạp Đầu Thưởng 100%

NO.1: Thưởng 100% lần nạp đầu tiên Thông thường, các khuyến mãi nạp tiền lần đầu đi kèm với yêu cầu vòng cược rất cao, thường từ 20 vòng trở lên. Tuy nhiên, ST666 hiểu rằng người chơi thường đắn đo khi quyết định nạp tiền vào sòng bài trực tuyến. Do đó, chúng tôi chỉ yêu cầu 8 vòng cược, cho phép người chơi rút tiền một cách nhanh chóng trong vòng 5 phút.

Thưởng 100% khi Đăng Nhập ST666

NO.2: Thưởng 16% mỗi ngày ST666 mang đến cho bạn một ưu đãi không thể bỏ lỡ. Mỗi khi bạn nạp tiền vào tài khoản hàng ngày, bạn sẽ được nhận thêm 16% số tiền nạp. Đây là cơ hội tuyệt vời dành cho những ai yêu thích cá cược trực tuyến và muốn gia tăng cơ hội chiến thắng của mình.

Bảo Hiểm Hoàn 10% Mỗi Ngày

NO.3: Bảo hiểm hoàn tiền 10% ST666 không chỉ hỗ trợ người chơi trong những lần may mắn mà còn luôn đồng hành khi bạn không gặp may. Chương trình khuyến mãi “bảo hiểm hoàn tiền 10% tổng tiền nạp mỗi ngày” là cách chúng tôi khích lệ và động viên tinh thần game thủ, giúp bạn tiếp tục hành trình chinh phục các thử thách cá cược.

Giới Thiệu Bạn Bè Thưởng 999K

NO.4: Giới thiệu bạn bè – Thưởng 999K Chương trình “Giới thiệu bạn bè” của ST666 giúp bạn có cơ hội cá cược cùng bạn bè và người thân. Không những vậy, bạn còn có thể nhận được phần thưởng lên đến 999K khi giới thiệu người bạn của mình tham gia ST666. Đây chính là một ưu đãi tuyệt vời giúp bạn vừa có thêm người đồng hành, vừa nhận được thưởng hấp dẫn.

Đăng Nhập Nhận Ngay 280K

NO.5: Điểm danh nhận thưởng 280K Nếu bạn là thành viên thường xuyên của ST666, hãy đừng quên nhấp vào hộp quà hàng ngày để điểm danh. Chỉ cần đăng nhập liên tục trong 7 ngày, cơ hội nhận thưởng 280K sẽ thuộc về bạn!

Kết Luận

ST666 luôn nỗ lực không ngừng để mang lại những chương trình khuyến mãi hấp dẫn và thiết thực nhất cho người chơi. Dù bạn là người mới hay đã gắn bó lâu năm với nền tảng, ST666 cam kết cung cấp trải nghiệm cá cược tốt nhất, an toàn và công bằng. Hãy tham gia ngay để không bỏ lỡ các cơ hội tuyệt vời từ ST666!

Интересная информационнная статья общей тематики.

https://katebschool.edu.af/teachers

Информационный сайт с интересной темы.

https://www.ricsfeet.com/2023/11/18/beer-oclock

Интересные и увлекательные статьи у нас.

https://www.gapvisaservices.com.au/study-visa/country-to-offer-point-based-immigrations-2

Интересные статьи на данном сайте.

https://networkbuildz.com/t-mobile-transfer-pin

Интересная информационнная статья медицинской тематики.

https://twoplus3.in/different-types-of-artificial-grass-in-uae

Статьи на различные темы на страницах сайта.

https://www.noemataintl.com/gmedia/design-7-jpg

bc game mirror site

Прикольные мемы http://shutki-anekdoty.ru/kartinki-prikolnye.

NAGAEMPIRE: Platform Sports Game dan E-Games Terbaik di Tahun 2024

Selamat datang di Naga Empire, platform hiburan online yang menghadirkan pengalaman gaming terdepan di tahun 2024! Kami bangga menawarkan sports game, permainan kartu, dan berbagai fitur unggulan yang dirancang untuk memberikan Anda kesenangan dan keuntungan maksimal.

Keunggulan Pendaftaran dengan E-Wallet dan QRIS

Kami memprioritaskan kemudahan dan kecepatan dalam pengalaman bermain Anda:

Pendaftaran dengan E-Wallet: Daftarkan akun Anda dengan mudah menggunakan e-wallet favorit. Proses pendaftaran sangat cepat, memungkinkan Anda langsung memulai petualangan gaming tanpa hambatan.

QRIS Auto Proses dalam 1 Detik: Transaksi Anda diproses instan hanya dalam 1 detik dengan teknologi QRIS, memastikan pembayaran dan deposit berjalan lancar tanpa gangguan.

Sports Game dan Permainan Kartu Terbaik di Tahun 2024

Naga Empire menawarkan berbagai pilihan game menarik:

Sports Game Terlengkap: Dari taruhan olahraga hingga fantasy sports, kami menyediakan sensasi taruhan olahraga dengan kualitas terbaik.

Kartu Terbaik di 2024: Nikmati permainan kartu klasik hingga variasi modern dengan grafis yang menakjubkan, memberikan pengalaman bermain yang tak terlupakan.

Permainan Terlengkap dan Toto Terlengkap

Kami memiliki koleksi permainan yang sangat beragam:

Permainan Terlengkap: Temukan berbagai pilihan permainan seperti slot mesin, kasino, hingga permainan berbasis keterampilan, semua tersedia di Naga Empire.

Toto Terlengkap: Layanan Toto Online kami menawarkan pilihan taruhan yang lengkap dengan odds yang kompetitif, memberikan pengalaman taruhan yang optimal.

Bonus Melimpah dan Turnover Terendah

Bonus Melimpah: Dapatkan bonus mulai dari bonus selamat datang, bonus setoran, hingga promosi eksklusif. Kami selalu memberikan nilai lebih pada setiap taruhan Anda.

Turnover Terendah: Dengan turnover rendah, Anda dapat meraih kemenangan lebih mudah dan meningkatkan keuntungan dari setiap permainan.

Naga Empire adalah tempat yang tepat bagi Anda yang mencari pengalaman gaming terbaik di tahun 2024. Bergabunglah sekarang dan rasakan sensasi kemenangan di platform yang paling komprehensif!

rgbet77

Bạn đang tìm kiếm những trò chơi hot nhất và thú vị nhất tại sòng bạc trực tuyến? RGBET tự hào giới thiệu đến bạn nhiều trò chơi cá cược đặc sắc, bao gồm Baccarat trực tiếp, máy xèng, cá cược thể thao, xổ số và bắn cá, mang đến cho bạn cảm giác hồi hộp đỉnh cao của sòng bạc! Dù bạn yêu thích các trò chơi bài kinh điển hay những máy xèng đầy kịch tính, RGBET đều có thể đáp ứng mọi nhu cầu giải trí của bạn.

RGBET Trò Chơi của Chúng Tôi

Bạn đang tìm kiếm những trò chơi hot nhất và thú vị nhất tại sòng bạc trực tuyến? RGBET tự hào giới thiệu đến bạn nhiều trò chơi cá cược đặc sắc, bao gồm Baccarat trực tiếp, máy xèng, cá cược thể thao, xổ số và bắn cá, mang đến cảm giác hồi hộp đỉnh cao của sòng bạc! Dù bạn yêu thích các trò chơi bài kinh điển hay những máy xèng đầy kịch tính, RGBET đều có thể đáp ứng mọi nhu cầu giải trí của bạn.

RGBET Trò Chơi Đa Dạng

Thể thao: Cá cược thể thao đa dạng với nhiều môn từ bóng đá, tennis đến thể thao điện tử.

Live Casino: Trải nghiệm Baccarat, Roulette, và các trò chơi sòng bài trực tiếp với người chia bài thật.

Nổ hũ: Tham gia các trò chơi nổ hũ với tỷ lệ trúng cao và cơ hội thắng lớn.

Lô đề: Đặt cược lô đề với tỉ lệ cược hấp dẫn.

Bắn cá: Bắn cá RGBET mang đến cảm giác chân thực và hấp dẫn với đồ họa tuyệt đẹp.

RGBET – Máy Xèng Hấp Dẫn Nhất

Khám phá các máy xèng độc đáo tại RGBET với nhiều chủ đề khác nhau và tỷ lệ trả thưởng cao. Những trò chơi nổi bật bao gồm:

RGBET Super Ace

RGBET Đế Quốc Hoàng Kim

RGBET Pharaoh Treasure

RGBET Quyền Vương

RGBET Chuyên Gia Săn Rồng

RGBET Jackpot Fishing

Vì sao nên chọn RGBET?

RGBET không chỉ cung cấp hàng loạt trò chơi đa dạng mà còn mang đến một hệ thống cá cược an toàn và chuyên nghiệp, đảm bảo mọi quyền lợi của người chơi:

Tốc độ nạp tiền nhanh chóng: Chuyển khoản tại RGBET chỉ mất vài phút và tiền sẽ vào tài khoản ngay lập tức, giúp bạn không bỏ lỡ bất kỳ cơ hội nào.

Game đổi thưởng phong phú: Từ cá cược thể thao đến slot game, RGBET cung cấp đầy đủ trò chơi giúp bạn tận hưởng mọi phút giây thư giãn.

Bảo mật tuyệt đối: Với công nghệ mã hóa tiên tiến, tài khoản và tiền vốn của bạn sẽ luôn được bảo vệ một cách an toàn.

Hỗ trợ đa nền tảng: Bạn có thể chơi trên mọi thiết bị, từ máy tính, điện thoại di động (iOS/Android), đến nền tảng H5.

Tải Ứng Dụng RGBET và Nhận Khuyến Mãi Lớn

Hãy tham gia RGBET ngay hôm nay để tận hưởng thế giới giải trí không giới hạn với các trò chơi thể thao, thể thao điện tử, casino trực tuyến, xổ số, và slot game. Quét mã QR và tải ứng dụng RGBET trên điện thoại để trải nghiệm game tốt hơn và nhận nhiều khuyến mãi hấp dẫn!

Tham gia RGBET để bắt đầu cuộc hành trình cá cược đầy thú vị ngay hôm nay!

st666

ST666 – Nhà Cái Uy Tín Với Nhiều Khuyến Mãi Hấp Dẫn

ST666 là một trong những sòng bài trực tuyến uy tín nhất, mang đến cho các thành viên nhiều chương trình khuyến mãi đa dạng và hấp dẫn. Chúng tôi luôn hy vọng rằng những ưu đãi đặc biệt này sẽ mang lại trải nghiệm cá cược tuyệt vời cho tất cả thành viên của mình.

Khuyến Mãi Nạp Đầu Thưởng 100%

NO.1: Thưởng 100% lần nạp đầu tiên Thông thường, các khuyến mãi nạp tiền lần đầu đi kèm với yêu cầu vòng cược rất cao, thường từ 20 vòng trở lên. Tuy nhiên, ST666 hiểu rằng người chơi thường đắn đo khi quyết định nạp tiền vào sòng bài trực tuyến. Do đó, chúng tôi chỉ yêu cầu 8 vòng cược, cho phép người chơi rút tiền một cách nhanh chóng trong vòng 5 phút.

Thưởng 100% khi Đăng Nhập ST666

NO.2: Thưởng 16% mỗi ngày ST666 mang đến cho bạn một ưu đãi không thể bỏ lỡ. Mỗi khi bạn nạp tiền vào tài khoản hàng ngày, bạn sẽ được nhận thêm 16% số tiền nạp. Đây là cơ hội tuyệt vời dành cho những ai yêu thích cá cược trực tuyến và muốn gia tăng cơ hội chiến thắng của mình.

Bảo Hiểm Hoàn 10% Mỗi Ngày

NO.3: Bảo hiểm hoàn tiền 10% ST666 không chỉ hỗ trợ người chơi trong những lần may mắn mà còn luôn đồng hành khi bạn không gặp may. Chương trình khuyến mãi “bảo hiểm hoàn tiền 10% tổng tiền nạp mỗi ngày” là cách chúng tôi khích lệ và động viên tinh thần game thủ, giúp bạn tiếp tục hành trình chinh phục các thử thách cá cược.

Giới Thiệu Bạn Bè Thưởng 999K

NO.4: Giới thiệu bạn bè – Thưởng 999K Chương trình “Giới thiệu bạn bè” của ST666 giúp bạn có cơ hội cá cược cùng bạn bè và người thân. Không những vậy, bạn còn có thể nhận được phần thưởng lên đến 999K khi giới thiệu người bạn của mình tham gia ST666. Đây chính là một ưu đãi tuyệt vời giúp bạn vừa có thêm người đồng hành, vừa nhận được thưởng hấp dẫn.

Đăng Nhập Nhận Ngay 280K

NO.5: Điểm danh nhận thưởng 280K Nếu bạn là thành viên thường xuyên của ST666, hãy đừng quên nhấp vào hộp quà hàng ngày để điểm danh. Chỉ cần đăng nhập liên tục trong 7 ngày, cơ hội nhận thưởng 280K sẽ thuộc về bạn!

Kết Luận

ST666 luôn nỗ lực không ngừng để mang lại những chương trình khuyến mãi hấp dẫn và thiết thực nhất cho người chơi. Dù bạn là người mới hay đã gắn bó lâu năm với nền tảng, ST666 cam kết cung cấp trải nghiệm cá cược tốt nhất, an toàn và công bằng. Hãy tham gia ngay để không bỏ lỡ các cơ hội tuyệt vời từ ST666!

Наша миссия — сделать процесс поиска и оформления микрозаймов в Казахстане максимально простым и прозрачным. Мы не только предоставляем актуальную информацию о различных кредитных предложениях, но и консультируем клиентов по всем вопросам, связанным с оформлением микрозаймов. Благодаря нашему опыту и знаниям рынка, мы помогаем клиентам избежать скрытых комиссий и выбрать наиболее выгодные и прозрачные условия.

микро займы онлайн займы .

Старые срубные дома — это не только воспоминание о прошлом, но и уникальные архитектурные постройки, которые нуждаются в уходе. Ремонт таких домов основывается на особом подходе, так как консервация первоначальных элементов конструкции и использование безопасных материалов остаются приоритетом. https://masterpomebeli.ru/svezhie-publikacii/remont-terrasy-i-verand-kak-zashhitit-ot-pogodnyx-uslovij.html – Обновление сгнивших строительных элементов, восстановление фундамента, восстановление оконных рам и кровли — все эти действия должны выполняться с учётом особенностей деревянного строительства, чтобы поддержать эстетику и долговечность дома.

Расширение сельскому дому — это ещё одна ключевая задача, с которой приходят к владельцы малых строений. Чтобы расширить жилое пространство, можно добавить веранду, террасу или даже полноценную дополнительную комнату. При этом важно учитывать гармонию между свежими конструкциями и оригинальной частью здания. Использование технологичных строительных материалов способствует повысить теплоизоляцию и оптимизировать затраты на отопление, что особенно целесообразно в условиях сезонного проживания.

Кроме того, следует заметить на важность согласования подобных действий с местными властями. Иногда увеличение площади нуждается оформления согласований и предварительного оформления проектной документации. Следует придерживаться строительные нормы и инструкции, чтобы снизить возможных трудностей в перспективе. Эксперты всегда готовы помочь подготовить проект, который будет удовлетворять не только личным пожеланиям, но и всем юридическим и строительным аспектам.

Таким образом, реконструкция и увеличение площади летнего дома — это не просто шаги модернизации объекта, но и способ сделать его более уютным и функциональным. Защита наследия брусового строительства и использование инновационных технологий позволят обновить дом новый вид, не сохраняя его оригинального характера.

Старые брусовые дома — это не только воспоминание о прошлом, но и неповторимые архитектурные сооружения, которые испытывают потребность в уходе. Ремонт таких домов предполагает особом подходе, так как консервация исходных элементов конструкции и использование натуральных материалов служат основной задачей. https://1landscapedesign.ru/drenazh/probljemy-drjenazha-i-vodootvoda-v-zagorodnom-domje.html – Замена сгнивших балок, поддержание фундамента, обновление оконных рам и кровли — все эти работы должны осуществляться с рассмотрением особенностей срубного строительства, чтобы сберечь привлекательность и продолжительность службы дома.

Расширение площади дачному дому — это ещё одна значимая задача, с которой приходят к собственники малых строений. Чтобы увеличить жилое пространство, можно пристроить веранду, террасу или даже полноценную дополнительную комнату. При этом следует соблюдать гармонию между дополнительными конструкциями и старой частью постройки. Применение технологичных конструкционных материалов способствует модернизировать теплоизоляцию и сократить расходные статьи на обогревательные системы, что особенно важно в ситуации сезонного проживания.

Кроме того, нужно заметить на важность согласования подобных переделок с региональными властями. Иногда расширение требует оформления лицензий и подготовки проектной документации. Важно выполнять архитектурные требования и рекомендации, чтобы снизить возможных проблем в наступающем времени. Специалисты помогут подготовить проект, который будет учитывать не только частным требованиям, но и всем законодательным и инженерным аспектам.

Таким образом, реконструкция и расширение летнего дома — это не просто деятельность реставрации объекта, но и шанс сделать его удобным и удобным для проживания. Поддержание устоев срубного строительства и применение актуальных технологий дадут возможность освежить постройку новый вид, не утратив его особенного очарования.

Полезная информация на сайте. Все что вы хоте знать об интернете полезный сервис

Запой — это состояние, характеризующееся продолжительным и интенсивным употреблением алкоголя, которое приводит к негативным изменениям в организме и психике человека. Алкогольная зависимость — это серьезное заболевание, требующее профессиональной помощи. Вывод из запоя — это первый шаг на пути к выздоровлению, который должен быть выполнен с максимальной осторожностью и квалифицированным сопровождением.

Подробнее можно узнать тут – вывод из запоя на дому заволжье

Процедура вывода из запоя на дому включает в себя комплекс мероприятий, направленных на восстановление нормального состояния пациента. Данный подход часто применяется, когда стационарное лечение нецелесообразно или невозможно по ряду причин, таких как отсутствие возможности оставить работу или семейные обязательства.

Получить дополнительную информацию – вывод из запоя иваново на дому круглосуточно

Наркологическая клиника “Ренессанс” — специализированное медицинское учреждение, предназначенное для оказания помощи лицам, страдающим от алкогольной и наркотической зависимости. Наша цель — предоставить эффективные методы лечения и поддержку, чтобы помочь пациентам преодолеть пагубное пристрастие и вернуть их к здоровой и полноценной жизни.

Выяснить больше – вывод из запоя на дому набережные

Запой представляет собой критическое состояние, связанное с длительным употреблением алкоголя. Это явление приводит к развитию физической и психической зависимости, что значительно ухудшает качество жизни. Вывод из запоя в стационаре необходим для восстановления здоровья пациента. В данной статье рассматриваются ключевые аспекты анонимного вывода, скорость лечения, а также роль нарколога в процессе реабилитации.

Ознакомиться с деталями – вывод из запоя в стационаре в архангельске

В наркологической практике применяют два основных метода купирования запойных состояний: стационарное лечение и вывод из запоя на дому. Выбор метода определяется врачом-наркологом с учётом тяжести абстинентного синдрома, наличия сопутствующей патологии, возраста пациента, а также его пожеланий.

Подробнее – вывод из запоя анонимно наро фоминск

Во-первых, конечная сумма зависит от удалённости места проведения манипуляций. Чем дальше находится медицинский центр от адреса пациента, тем выше цена. Во-вторых, тяжесть состояния, в котором находится больной, также влияет на финансовые затраты. При необходимости более сложных манипуляций или применения специфических препаратов цена может возрасти. В среднем, стоимость колеблется от 6000 до 25000 рублей.

Получить дополнительные сведения – вывод из запоя цены на дому мытищи

สล็อต888 เป็นหนึ่งในแพลตฟอร์มเกมสล็อตออนไลน์ที่ได้รับความนิยมสูงสุดในปัจจุบัน โดยมีความโดดเด่นด้วยการให้บริการเกมสล็อตที่หลากหลายและมีคุณภาพ รวมถึงฟีเจอร์ที่ช่วยให้ผู้เล่นสามารถเพลิดเพลินกับการเล่นได้อย่างเต็มที่ ในบทความนี้ เราจะมาพูดถึงฟีเจอร์และจุดเด่นของสล็อต888 ที่ทำให้เว็บไซต์นี้ได้รับความนิยมเป็นอย่างมาก

ฟีเจอร์เด่นของ PG สล็อต888

ระบบฝากถอนเงินอัตโนมัติที่รวดเร็ว สล็อต888 ให้บริการระบบฝากถอนเงินแบบอัตโนมัติที่สามารถทำรายการได้ทันที ไม่ต้องรอนาน ไม่ว่าจะเป็นการฝากหรือถอนก็สามารถทำได้ภายในไม่กี่วินาที รองรับการใช้งานผ่านทรูวอลเล็ทและช่องทางอื่น ๆ โดยไม่มีขั้นต่ำในการฝากถอน

รองรับทุกอุปกรณ์ ทุกแพลตฟอร์ม ไม่ว่าคุณจะเล่นจากอุปกรณ์ใดก็ตาม สล็อต888 รองรับทั้งคอมพิวเตอร์ แท็บเล็ต และสมาร์ทโฟน ไม่ว่าจะเป็นระบบ iOS หรือ Android คุณสามารถเข้าถึงเกมสล็อตได้ทุกที่ทุกเวลาเพียงแค่มีอินเทอร์เน็ต

โปรโมชั่นและโบนัสมากมาย สำหรับผู้เล่นใหม่และลูกค้าประจำ สล็อต888 มีโปรโมชั่นต้อนรับ รวมถึงโบนัสพิเศษ เช่น ฟรีสปินและโบนัสเครดิตเพิ่ม ทำให้การเล่นเกมสล็อตกับเราเป็นเรื่องสนุกและมีโอกาสทำกำไรมากยิ่งขึ้น

ความปลอดภัยสูงสุด เรื่องความปลอดภัยเป็นสิ่งที่สล็อต888 ให้ความสำคัญเป็นอย่างยิ่ง เราใช้เทคโนโลยีการเข้ารหัสข้อมูลขั้นสูงเพื่อปกป้องข้อมูลส่วนบุคคลของลูกค้า ระบบฝากถอนเงินยังมีมาตรการรักษาความปลอดภัยที่เข้มงวด ทำให้ลูกค้ามั่นใจในการใช้บริการกับเรา

ทดลองเล่นสล็อตฟรี

สล็อต888 ยังมีบริการให้ผู้เล่นสามารถทดลองเล่นสล็อตได้ฟรี ซึ่งเป็นโอกาสที่ดีในการทดลองเล่นเกมต่าง ๆ ที่มีอยู่บนเว็บไซต์ เช่น Phoenix Rises, Dream Of Macau, Ways Of Qilin, Caishens Wins และเกมยอดนิยมอื่น ๆ ที่มีกราฟิกสวยงามและรูปแบบการเล่นที่น่าสนใจ

ไม่ว่าจะเป็นเกมแนวผจญภัย เช่น Rise Of Apollo, Dragon Hatch หรือเกมที่มีธีมแห่งความมั่งคั่งอย่าง Crypto Gold, Fortune Tiger, Lucky Piggy ทุกเกมได้รับการออกแบบมาเพื่อสร้างประสบการณ์การเล่นที่น่าจดจำและเต็มไปด้วยความสนุกสนาน

บทสรุป

สล็อต888 เป็นแพลตฟอร์มที่ครบเครื่องเรื่องเกมสล็อตออนไลน์ ด้วยฟีเจอร์ที่ทันสมัย โปรโมชั่นที่น่าสนใจ และระบบรักษาความปลอดภัยที่เข้มงวด ทำให้คุณมั่นใจได้ว่าการเล่นกับสล็อต888 จะเป็นประสบการณ์ที่ปลอดภัยและเต็มไปด้วยความสนุก

Веселые анекдоты http://shutki-anekdoty.ru/anekdoty.

Интересная информационнная статья общей тематики.

https://cbcanada.net/how-where-to-market-your-ico-startup

Информационный сайт с интересной темы.

https://jade-kite.com/how-to-build-a-solid-brand-from-scratch

Интересные статьи на данном сайте.

https://www.aspgraphy.3pixls.com/pink-petals-photo-overlays

Интересные и увлекательные статьи у нас.

https://www.jordanfilmrental.com/2022/08/31/mutually-beneficial-connections-old-men-dating-sites-just-for-seeking-newer-women

Интересная информационнная статья медицинской тематики.

http://blogs.lwhs.org/bayareacinema/2015/03/12/hello-world

Статьи на различные темы на страницах сайта.

https://depostjateng.com/opini/cara-untuk-menghilangkan-bau-ketiak

Those on a pay-as-you-go mobile phone contract in the

UK can also use the pay-by-phone bill option.

สล็อต888 เป็นหนึ่งในแพลตฟอร์มเกมสล็อตออนไลน์ที่ได้รับความนิยมสูงสุดในปัจจุบัน โดยมีความโดดเด่นด้วยการให้บริการเกมสล็อตที่หลากหลายและมีคุณภาพ รวมถึงฟีเจอร์ที่ช่วยให้ผู้เล่นสามารถเพลิดเพลินกับการเล่นได้อย่างเต็มที่ ในบทความนี้ เราจะมาพูดถึงฟีเจอร์และจุดเด่นของสล็อต888 ที่ทำให้เว็บไซต์นี้ได้รับความนิยมเป็นอย่างมาก

ฟีเจอร์เด่นของ PG สล็อต888

ระบบฝากถอนเงินอัตโนมัติที่รวดเร็ว สล็อต888 ให้บริการระบบฝากถอนเงินแบบอัตโนมัติที่สามารถทำรายการได้ทันที ไม่ต้องรอนาน ไม่ว่าจะเป็นการฝากหรือถอนก็สามารถทำได้ภายในไม่กี่วินาที รองรับการใช้งานผ่านทรูวอลเล็ทและช่องทางอื่น ๆ โดยไม่มีขั้นต่ำในการฝากถอน

รองรับทุกอุปกรณ์ ทุกแพลตฟอร์ม ไม่ว่าคุณจะเล่นจากอุปกรณ์ใดก็ตาม สล็อต888 รองรับทั้งคอมพิวเตอร์ แท็บเล็ต และสมาร์ทโฟน ไม่ว่าจะเป็นระบบ iOS หรือ Android คุณสามารถเข้าถึงเกมสล็อตได้ทุกที่ทุกเวลาเพียงแค่มีอินเทอร์เน็ต

โปรโมชั่นและโบนัสมากมาย สำหรับผู้เล่นใหม่และลูกค้าประจำ สล็อต888 มีโปรโมชั่นต้อนรับ รวมถึงโบนัสพิเศษ เช่น ฟรีสปินและโบนัสเครดิตเพิ่ม ทำให้การเล่นเกมสล็อตกับเราเป็นเรื่องสนุกและมีโอกาสทำกำไรมากยิ่งขึ้น

ความปลอดภัยสูงสุด เรื่องความปลอดภัยเป็นสิ่งที่สล็อต888 ให้ความสำคัญเป็นอย่างยิ่ง เราใช้เทคโนโลยีการเข้ารหัสข้อมูลขั้นสูงเพื่อปกป้องข้อมูลส่วนบุคคลของลูกค้า ระบบฝากถอนเงินยังมีมาตรการรักษาความปลอดภัยที่เข้มงวด ทำให้ลูกค้ามั่นใจในการใช้บริการกับเรา

ทดลองเล่นสล็อตฟรี

สล็อต888 ยังมีบริการให้ผู้เล่นสามารถทดลองเล่นสล็อตได้ฟรี ซึ่งเป็นโอกาสที่ดีในการทดลองเล่นเกมต่าง ๆ ที่มีอยู่บนเว็บไซต์ เช่น Phoenix Rises, Dream Of Macau, Ways Of Qilin, Caishens Wins และเกมยอดนิยมอื่น ๆ ที่มีกราฟิกสวยงามและรูปแบบการเล่นที่น่าสนใจ

ไม่ว่าจะเป็นเกมแนวผจญภัย เช่น Rise Of Apollo, Dragon Hatch หรือเกมที่มีธีมแห่งความมั่งคั่งอย่าง Crypto Gold, Fortune Tiger, Lucky Piggy ทุกเกมได้รับการออกแบบมาเพื่อสร้างประสบการณ์การเล่นที่น่าจดจำและเต็มไปด้วยความสนุกสนาน

บทสรุป

สล็อต888 เป็นแพลตฟอร์มที่ครบเครื่องเรื่องเกมสล็อตออนไลน์ ด้วยฟีเจอร์ที่ทันสมัย โปรโมชั่นที่น่าสนใจ และระบบรักษาความปลอดภัยที่เข้มงวด ทำให้คุณมั่นใจได้ว่าการเล่นกับสล็อต888 จะเป็นประสบการณ์ที่ปลอดภัยและเต็มไปด้วยความสนุก

Профессиональный сервисный центр по ремонту моноблоков iMac в Москве.

Мы предлагаем: сервис по ремонту аймаков

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

Профессиональный сервисный центр по ремонту сотовых телефонов в Москве.

Мы предлагаем: мастер по ремонту ноутбуков москва

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

Статьи на различные темы на страницах сайта.

https://azulferri.com/?p=353

Цена выведения из запоя на дому может варьироваться от 3000 до 15 000 рублей. Данный метод предполагает оказание медицинской помощи пациенту в привычной домашней среде. Выездная бригада врачей проводит осмотр и оценку состояния, включая измерение жизненно важных показателей и анализ анамнеза.

Узнать больше – вывод из запоя славянск на кубани цены

Анонимность важна для пациентов, которые боятся стигматизации и не хотят оглашать свои проблемы с алкоголем. Она позволяет человеку получить необходимую медицинскую помощь, не опасаясь суждения со стороны общественности. Важно отметить, что анонимность не означает отсутствие конфиденциальности. Вся информация о пациенте хранится в строгой тайне и доступна только медицинскому персоналу.

Получить больше информации – вывод из запоя в орле в стационаре

Стационарное лечение подразумевает госпитализацию в специализированное медицинское учреждение. Этот метод рекомендуется при выраженной зависимости, когда требуется постоянный мониторинг состояния пациента. Госпитализация позволяет обеспечить круглосуточный контроль, что особенно актуально в случаях тяжелых симптомов абстиненции. На начальном этапе производится комплексное медицинское обследование, включая анализы крови и функциональные тесты, для оценки состояния органов.

Детальнее – вывод из запоя витебск на дому анонимно

Срочный вывод из запоя необходим в ситуациях, когда наблюдаются угрожающие состояния здоровья. Признаки, указывающие на необходимость экстренной медицинской помощи, могут включать выраженный тремор, усиленное потоотделение, галлюцинации и состояние тревожности. В таких случаях важно незамедлительное обращение к медицинским специалистам, так как игнорирование симптомов может привести к серьёзным последствиям.

Узнать больше – вывод из запоя альметьевск круглосуточно

Круглосуточные услуги вывода из запоя на дому позволяют пациентам получить необходимую медицинскую помощь в любое время суток. Эта возможность особенно важна для людей, находящихся в состоянии острого алкогольного опьянения или испытывающих симптомы абстиненции.

Изучить вопрос глубже – вывод из запоя на дому цены волгоград

Современное общество сталкивается с серьёзными вызовами, связанными с зависимостями. Проблемы, возникающие в результате злоупотребления психоактивными веществами, охватывают не только здоровье, но также влияют на социальные отношения и качество жизни. Наркологическая клиника “Точка опоры” предлагает широкий спектр услуг, направленных на восстановление и реабилитацию людей, столкнувшихся с этими трудностями.

Получить дополнительные сведения – вывод из запоя bystro med быстро мед

Kometa Casino: Превосходный выбор для любителей азартного досуга

В случае если вы интересуетесь азартными играми и рассматриваете площадку, которая предлагает большой выбор игровых автоматов и живых казино, а к тому же щедрые бонусы, Казино Kometa — это то место, в котором вас ждут яркие эмоции. Попробуем изучим, что превращает это казино выдающимся и по каким причинам клиенты отдают предпочтение его для своих развлечений.

### Ключевые черты Kometa Casino

Казино Kometa — это всемирная платформа, которая была запущена в 2024 году и уже сейчас завоевала интерес пользователей по всему миру. Вот основные факты, что выделяют данную платформу:

Характеристика Описание

Дата запуска Год основания 2024

Глобальная доступность Международная

Количество Игр Больше тысячи

Сертификация Кюрасао

Мобильный доступ Да

Способы Оплаты Visa, Mastercard, Skrill

Поддержка 24 часа в сутки

Специальные предложения Акции и бонусы

Защита данных Шифрование SSL

### Что привлекает в Казино Kometa?

#### Программа лояльности

Одним из ключевых функций Kometa Casino становится уникальная программа лояльности. Чем активнее играете, тем больше ваши вознаграждения. Система состоит из 7 этапов:

– **Земля (уровень 1)**: Кэшбек 3% 3% от потраченных средств за 7 дней.

– **Уровень 2 — Луна**: 5% кэшбек при ставках от 5 000 до 10 000 RUB.

– **Уровень 3 — Венера**: Кэшбек 7% при ставках на сумму от 10 001 до 50 000 ?.

– **Марс (уровень 4)**: 8% кэшбек при сумме ставок от 50 001 до 150 000 ?.

– **Уровень 5 — Юпитер**: Возврат 10% при общей ставке свыше 150 000 RUB.

– **Сатурн (уровень 6)**: Возврат 11%.

– **Уран (уровень 7)**: Максимальный возврат до 12%.

#### Акции и возврат средств

Для сохранения высокого уровня азарта, Kometa Casino предлагает регулярные бонусы, кэшбек и фриспины для всех новых игроков. Постоянные подарки способствуют сохранять интерес на протяжении всей игры.

#### Большое количество развлечений

Огромное количество развлечений, включая слоты, настольные развлечения и игры с живыми дилерами, создают Казино Kometa площадкой, где каждый найдет развлечение на вкус. Вы можете наслаждаться стандартными автоматами, и современными слотами от ведущих провайдеров. Дилеры в реальном времени придают играм настоящее казино, формируя атмосферу азартного дома.

Алкогольный запой представляет собой серьезное состояние, требующее незамедлительного медицинского вмешательства. Стационарное лечение является оптимальным решением для эффективного и безопасного вывода из запоя, особенно в тяжелых случаях интоксикации. В этой статье мы подробно рассмотрим процесс стационарного лечения, его анонимность, скорость и роль нарколога в восстановлении пациентов.

Разобраться лучше – вывод из запоя в стационаре анонимно

Алкогольная интоксикация, или запой, представляет собой состояние, при котором организм человека испытывает серьезное воздействие этанола, что приводит к нарушению нормальной физиологической деятельности. Анонимный вывод из запоя — это процесс оказания медицинской помощи с соблюдением конфиденциальности, направленный на восстановление здоровья и избавление от последствий чрезмерного употребления алкоголя. В данной статье мы подробно рассмотрим современные методы лечения, их эффективность и важность сохранения анонимности в процессе выздоровления.

Изучить вопрос глубже – вывод из запоя анонимно иркутск

Клиника создана для оказания квалифицированной помощи всем, кто страдает от различных форм зависимости. Мы стремимся не только к лечению, но также к формированию здорового образа жизни, возвращая пациентов к полноценной жизни.

Получить дополнительную информацию – вывод из запоя в симферополе цены

Круглосуточная помощь при запое подразумевает возможность получения медицинской поддержки в любое время суток. Этот подход является крайне важным, поскольку состояние пациента может резко ухудшиться, требуя срочного вмешательства. Вывод из запоя на дому – удобный и эффективный метод, позволяющий пациенту чувствовать себя комфортно в привычной обстановке.

Получить дополнительную информацию – вывод из запоя на дому круглосуточно narkologypro

Вывод из запоя на дому — это процесс оказания медицинской помощи лицам, страдающим от алкогольной интоксикации, в комфортной домашней обстановке. Запой представляет собой состояние, при котором человек не может контролировать потребление алкоголя, что приводит к тяжелой интоксикации организма. Такое состояние требует своевременного и профессионального вмешательства, чтобы минимизировать риски для здоровья и жизни пациента.

Получить дополнительные сведения – вывод из запоя на дому омск отзывы

Цена выведения из запоя на дому может колебаться в диапазоне от 4000 до 18 000 рублей. Данный метод подразумевает оказание медицинской помощи пациенту в привычной домашней обстановке, что имеет свои преимущества. Выездная бригада врачей проводит осмотр и оценку состояния, измеряя жизненно важные показатели и анализируя анамнез пациента.

Ознакомиться с деталями – вывод из запоя цена щелково

Свежие приколы, шутки и картинки http://shutki-anekdoty.ru/.

Produzione video professionale https://orbispro.it creazione di spot pubblicitari, film aziendali e contenuti video. Ciclo completo di lavoro, dall’idea al montaggio. Soluzioni creative per promuovere con successo il tuo brand.

NAGAEMPIRE: Platform Sports Game dan E-Games Terbaik di Tahun 2024

Selamat datang di Naga Empire, platform hiburan online yang menghadirkan pengalaman gaming terdepan di tahun 2024! Kami bangga menawarkan sports game, permainan kartu, dan berbagai fitur unggulan yang dirancang untuk memberikan Anda kesenangan dan keuntungan maksimal.

Keunggulan Pendaftaran dengan E-Wallet dan QRIS

Kami memprioritaskan kemudahan dan kecepatan dalam pengalaman bermain Anda:

Pendaftaran dengan E-Wallet: Daftarkan akun Anda dengan mudah menggunakan e-wallet favorit. Proses pendaftaran sangat cepat, memungkinkan Anda langsung memulai petualangan gaming tanpa hambatan.

QRIS Auto Proses dalam 1 Detik: Transaksi Anda diproses instan hanya dalam 1 detik dengan teknologi QRIS, memastikan pembayaran dan deposit berjalan lancar tanpa gangguan.

Sports Game dan Permainan Kartu Terbaik di Tahun 2024

Naga Empire menawarkan berbagai pilihan game menarik:

Sports Game Terlengkap: Dari taruhan olahraga hingga fantasy sports, kami menyediakan sensasi taruhan olahraga dengan kualitas terbaik.

Kartu Terbaik di 2024: Nikmati permainan kartu klasik hingga variasi modern dengan grafis yang menakjubkan, memberikan pengalaman bermain yang tak terlupakan.

Permainan Terlengkap dan Toto Terlengkap

Kami memiliki koleksi permainan yang sangat beragam:

Permainan Terlengkap: Temukan berbagai pilihan permainan seperti slot mesin, kasino, hingga permainan berbasis keterampilan, semua tersedia di Naga Empire.

Toto Terlengkap: Layanan Toto Online kami menawarkan pilihan taruhan yang lengkap dengan odds yang kompetitif, memberikan pengalaman taruhan yang optimal.

Bonus Melimpah dan Turnover Terendah

Bonus Melimpah: Dapatkan bonus mulai dari bonus selamat datang, bonus setoran, hingga promosi eksklusif. Kami selalu memberikan nilai lebih pada setiap taruhan Anda.

Turnover Terendah: Dengan turnover rendah, Anda dapat meraih kemenangan lebih mudah dan meningkatkan keuntungan dari setiap permainan.

Naga Empire adalah tempat yang tepat bagi Anda yang mencari pengalaman gaming terbaik di tahun 2024. Bergabunglah sekarang dan rasakan sensasi kemenangan di platform yang paling komprehensif!

Смешные приколы, шутки и картинки http://shutki-anekdoty.ru/.

Cách Tối Đa Hóa Tiền Thưởng Tại RGBET

META title: Cách tối ưu hóa tiền thưởng trên RGBET

META description: Học cách tối đa hóa tiền thưởng của bạn trên RGBET bằng các mẹo và chiến lược cá cược hiệu quả nhất.

Giới thiệu

Tiền thưởng là cơ hội tuyệt vời để tăng cơ hội thắng lớn mà không phải bỏ ra nhiều vốn. RGBET cung cấp rất nhiều loại khuyến mãi hấp dẫn, hãy cùng khám phá cách tối ưu hóa chúng!

1. Đọc kỹ điều kiện khuyến mãi

Mỗi chương trình thưởng đều có điều kiện riêng, bạn cần đọc kỹ để đảm bảo không bỏ lỡ cơ hội.

2. Đặt cược theo mức yêu cầu

Để nhận thưởng, hãy đảm bảo rằng số tiền cược của bạn đạt yêu cầu tối thiểu.

3. Tận dụng tiền thưởng nạp đầu tiên

Đây là cơ hội để bạn có thêm vốn ngay từ đầu. Hãy lựa chọn mức nạp phù hợp với ngân sách.

4. Theo dõi khuyến mãi hàng tuần

RGBET liên tục đưa ra các chương trình khuyến mãi hàng tuần. Đừng bỏ lỡ cơ hội nhận thêm tiền thưởng!

5. Sử dụng điểm VIP

Khi bạn đạt mức VIP, điểm thưởng có thể được chuyển thành tiền mặt, giúp bạn tối ưu hóa lợi nhuận.

Kết luận

Biết cách tận dụng tiền thưởng không chỉ giúp bạn có thêm tiền cược mà còn tăng cơ hội thắng lớn.

Полезный сервис быстрого загона ссылок сайта в индексация поисковой системы – полезный сервис

Смешные приколы, шутки и картинки https://teletype.in/@anekdoty/prikoly-nastroenie.

This article is very insightful. I really appreciated the comprehensive analysis you shared.

It’s evident that you put a lot of research into producing this.

Looking forward to more of your posts. Grateful for

putting this out there. I’ll visit again to read more!

my web blog; Press release media (Stefanie)

Kometa Casino: Идеальный вариант для фанатов азартных игр

Если вы любите ставками и рассматриваете площадку, что предлагает огромный набор слотов и живых казино, а к тому же большие бонусы, Казино Kometa — это то место, на котором вас ждут незабываемый опыт. Предлагаем изучим, какие факторы превращает это казино выдающимся и по каким причинам клиенты выбирают этой платформе для игры.

### Главные особенности Kometa Casino

Kometa Casino — это международная игровая платформа, что была основана в 2024 году и уже привлекла признание пользователей по всему миру. Вот некоторые факты, что выделяют Kometa Casino:

Черта Детали

Год Основания Год основания 2024

География Доступа Глобальная

Число игр Больше тысячи

Лицензия Лицензия Кюрасао

Мобильный доступ Присутствует

Способы Оплаты Visa, Mastercard, Skrill

Поддержка 24/7 Чат и Email

Бонусы и Акции Щедрые бонусы

Система безопасности Шифрование SSL

### Почему выбирают Казино Kometa?

#### Бонусная система

Одним из интересных фишек Kometa Casino считается поощрительная программа. Чем больше вы играете, тем лучше призы и бонусы. Система состоит из семи уровней:

– **Уровень 1 — Земля**: Кэшбек 3% 3% от потраченных средств за 7 дней.

– **Уровень 2 — Луна**: 5% кэшбек на ставки от 5 000 до 10 000 RUB.

– **Уровень 3 — Венера**: Кэшбек 7% при ставках на сумму от 10 001 до 50 000 рублей.

– **Уровень 4 — Марс**: 8% бонуса при ставках от 50 001 до 150 000 ?.

– **Юпитер (уровень 5)**: Кэшбек 10% при общей ставке свыше 150 000 ?.

– **Уровень 6 — Сатурн**: 11% кэшбек.

– **Уровень 7 — Уран**: Максимальный кэшбек 12%.

#### Акции и возврат средств

Для сохранения азарт на высоте, Kometa Casino предоставляет еженедельные бонусы, кэшбек и бесплатные вращения для новичков. Регулярные вознаграждения обеспечивают удерживать внимание на каждой стадии игры.

#### Огромный каталог игр

Огромное количество развлечений, включая автоматы, карточные игры и живое казино, делают Казино Kometa местом, где любой найдет игру по душе. Вы можете наслаждаться классическими играми, так и новейшими играми от известных разработчиков. Прямые дилеры добавляют игровому процессу еще больше реализма, создавая атмосферу настоящего казино.

resume of a construction engineer resume of a design engineer

이용 안내 및 주요 정보

배송대행 이용방법

배송대행은 해외에서 구매한 상품을 중간지점(배대지)에 보내고, 이를 통해 한국으로 배송받는 서비스입니다. 먼저, 회원가입을 진행하고, 해당 배대지 주소를 이용해 상품을 주문한 후, 배송대행 신청서를 작성하여 배송 정보를 입력합니다. 모든 과정은 웹사이트를 통해 관리되며, 필요한 경우 고객센터를 통해 지원을 받을 수 있습니다.

구매대행 이용방법